[ad_1]

Touring post-war Germany in 1950, the thinker Hannah Arendt was struck by an obvious lack of ability of individuals to face the fact of their destroyed world: “Amid the ruins,” she wrote, “Germans mail one another image postcards nonetheless displaying cathedrals and market locations, the general public buildings that now not exist.”

Architecturally, Germany’s makes an attempt to face its cultural losses and reconcile the horrific current previous with an unknown future resulted in a variety of tendencies. There have been the Modernists who desired a whole break with a historical past that had culminated in anti-Trendy Hitlerism and as a substitute urged a tabula rasa elevating of a brand new materials world. Then there have been traditionalists who noticed the Third Reich as itself a product of rootless Modernity and yearned to reinstate a comforting, prelapsarian world.

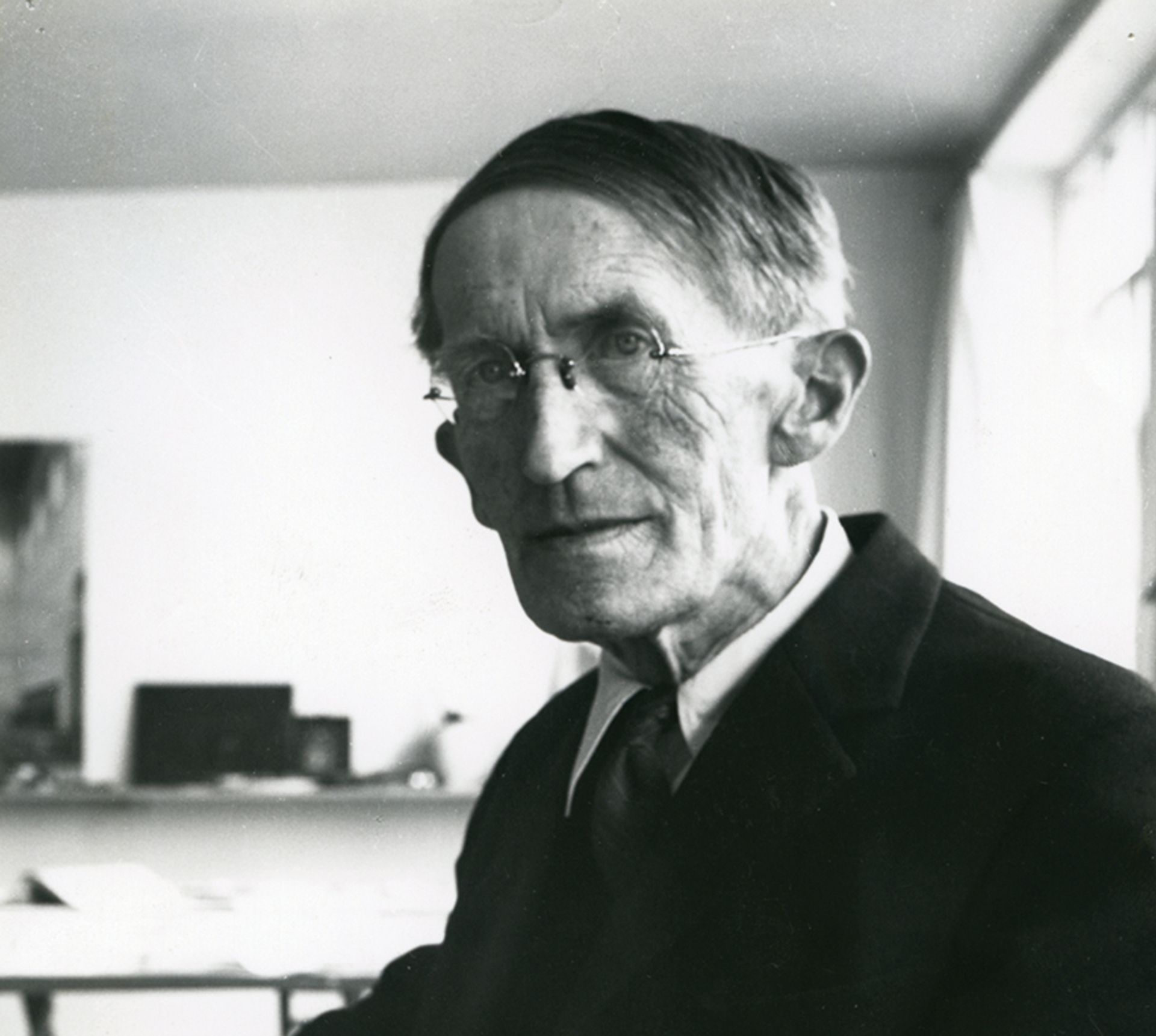

For Hans Döllgast, who died 50 years in the past this yr, pragmatism slightly than ideology at all times guided his constructing restoration tasks Architekturmuseum der TUM

Each approaches have been deployed at completely different occasions and in several German cities. Each ran the danger of erasing recollections and the bodily report of the fact of the Nazi interval. And with out recollections or proof, a reckoning with that previous turns into unimaginable.

Inventive reconstruction

The Bavarian architect Hans Döllgast (1891-1974), nevertheless, pioneered a minority third approach: crucial or artistic reconstruction, which takes a layered, collaged method to reconstruction. It advocated utilizing the fabric of the previous for its personal disposal, adapting broken locations in ways in which included the scars of battle, balancing preservation with renewal, reminiscence with forgetting—even when these goals have been usually not articulated. His was a removed from purist, archaeological conservationist method within the custom of John Ruskin or William Morris’s Society for the Safety of Historical Buildings.

Döllgast’s artistic repairs to Munich’s monuments, the place 60% of the outdated metropolis had been destroyed by Allied bombing, have been prime examples of excellent observe. However by the point he died in 1974, his artistic reconstruction method had largely been deserted. In Munich, the trads had received out, reconstructing a lot of the outdated metropolis in facsimile. Different German cities took a Modernist line. However prior to now decade, a “associates” organisation started to rearrange excursions and exhibitions of his work in Munich. And this summer season noticed a convention on the Technical College of Munich College of Engineering and Design marking the fiftieth anniversary of his demise.

In our century, the query of acceptable post-conflict reconstruction—and Döllgast’s classes—couldn’t be extra related. City warfare has savaged cities from Mosul, to Homs, Khan Yunis to Kharkiv. Throughout Europe, far-right nativists are funding pastiche reconstructions of not simply ruined however completely long-vanished castles, palaces and church buildings, creating mythic nationalist pasts as a way to culturally “different” these deemed to not belong. Lengthy-respected conservation requirements are being deserted. Budapest’s Unesco World Heritage Website is just one place amongst many whose materials authenticity is in danger from these fantasies.

A ‘comfortable’ Modernist

Döllgast started his profession working with Peter Behrens within the latter’s Expressionist section. He was a “comfortable” Modernist by no means doctrinaire or hostile to historical past and appreciative of different currents—Scandinavia’s interwar Classicism, for instance. He later labored on a variety of church tasks and started educating at Munich’s Technical College.

By no means clubbable, Döllgast most popular to work on the margins, though his apolitical, quiet-life moderation was craven in hindsight, permitting his profession to proceed beneath the Nazi regime—he was concerned on the town planning work for Nazi-colonised Poland. Whereas no dissident, he was deemed by the Allies “uncompromised” by Nazism.

Döllgast’s magnum opus is the reconstruction of the Alte Pinakothek, a neo-Renaissance palazzo constructed from 1826 to 1836 to accommodate the Bavarian royal artwork assortment. The highest-lit areas, a few of which have been proportioned to match the work displayed, have been pioneering. One third of the constructing was destroyed by wartime bombing and the rest left a burned-out shell. Amid the fierce reconstruction debates, Döllgast once more averted an ideological place, arguing pragmatically for his scheme on price effectivity grounds at a time when many needed the ruins of the museum (disparaged because the “outdated cabinet”) to be levelled. From 1946 onwards, he pushed for a collaged reconstruction for the Alte Pinakothek that used patched blockwork and blitz rubble to infill the ruins and which simplified detailing that blended slightly than aggressively juxtaposed new and outdated, whereas nonetheless sustaining a visible distinction between the surviving historic material and his light Modernist interventions.

He had already proved the value of his method at a smaller scale elsewhere in Munich, together with delicate metal and timber interventions within the broken pavilions of the town’s historic cemeteries.

After six years of campaigning, he received his approach and the Alte Pinakothek lastly reopened in 1957. His interventions included radical replanning that moved the doorway and put in an immense scala regia rather than a former colonnade.

The Cambridge College tutorial Maximilian Sternberg, who spoke on the Munich convention, and is writing a e-book on Döllgast, notes that he was crucial of the concept of taking aesthetic pleasure in ruins—what we’d right this moment name “wreck porn”—describing it as “pitiless”. He was as a substitute within the high quality of the originals.

In some respects, Döllgast’s “artistic reconstruction” has an affinity with that of Carlo Scarpa, who was remodelling Verona’s Castelvecchio Museum at an identical date. However his pragmatism slightly than zealotry meant that, regardless of some curiosity from the architects James Stirling and the Smithsons, he stays far less-known internationally. Extra just lately, David Chipperfield has been amongst Döllgast’s most outstanding champions. The Alte Pinakothek instantly knowledgeable Chipperfield’s reconstruction of the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Even so, Munich’s conservatives have lobbied repeatedly over many years to take away Döllgast’s progressive façades on the Alte Pinakothek and reinstate Nineteenth-century facsimiles. Amid an increase of nativism and nationalism throughout Europe—together with in architectural and heritage—Döllgast’s delicate third-way improvements supply a extra trustworthy approach ahead.

[ad_2]

Source link